By Dylan • 5 March 2021

Hello all and welcome to the final part of my three part series on the Prisoner video game. If you missed the first part where I outline what the video game is and tackle some of the apocrypha surrounding it, be sure to check it out here. In the second part I recounted a play through of the video game from my point of view, you can check that out over here. In this part I’m going to wrap up some final thoughts relating to the video game and its relationship with the television show upon which it is ostensibly based.

Remember how at the end of part 2 I said if everything went right I would have escaped the Island by now? Well, I did not. I failed. Miserably. I didn’t actually figure it out on my own, but to be fair the estimate is that The Prisoner is a 60 hour video game and I gave it less than half of that. I’m a busy man you see, I’ve got two podcasts a week to edit. Speaking of which, as of this post we’ll have started our podcast on The Prisoner (2009) so go ahead and go give it a listen, I’m exceedingly excited to see where it goes this season. But beyond just playing it, let me talk a little about some conclusions I have about The Prisoner, how successful (or not) it is at being a Prisoner adaptation, and doing a little meta fiction dive.

But let us return to a question I asked in the first part of this blog series. Is The Prisoner the first Meta fictional Video Game? And the answer to that is, I’m fairly certain, yes. I could find no evidence in any of my research that any game before this one did a lot of the things that this one does in the vein of exploiting the meta fiction of the medium. The first Metal Gear, probably the next closest I could think of, wasn’t published until 1987, a full 6 years after the first version of The Prisoner.

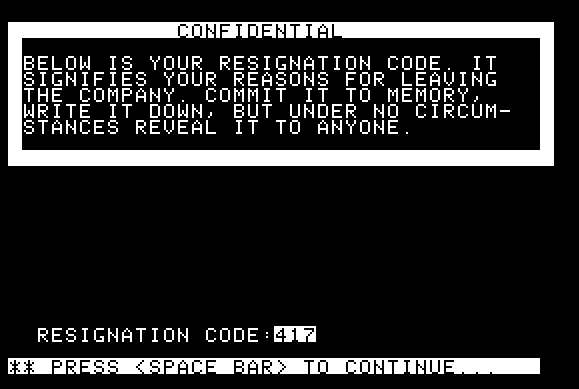

And we should talk about that, because you may be surprised to learn that by the writing of this article, The Prisoner is not listed on the Wikipedia list of “Metafictional video games.” Which is a bit of a shocker because it really does delve into some really really trippy things. I’ve already talked about the one, in my very first blog post. In that post I mention that some versions of Prisoner 2 will fake a crash on a line number corresponding to your reason for resigning in an attempt to get you to input your reason for resigning into the crash window. Devious, I know. But think about that for a second. This is something that wouldn’t work in any other medium. A Prisoner book can’t just fake a crash. You can’t even interact with a Prisoner book in the same way. The Prisoner video game exploits the fact that it is a video game in order to defeat you. It would be like if the opponent king on a chess board decided to start jumping up and down to try shake the board enough to tip your king over (tipping your king is a resignation in chess), thus exploiting the physical nature of your chess game to defeat you outside the prescribed rules of the games.

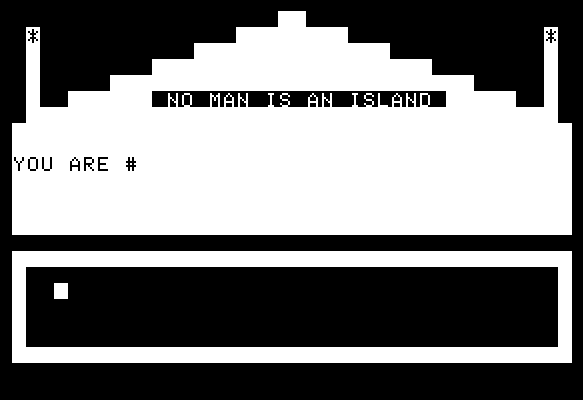

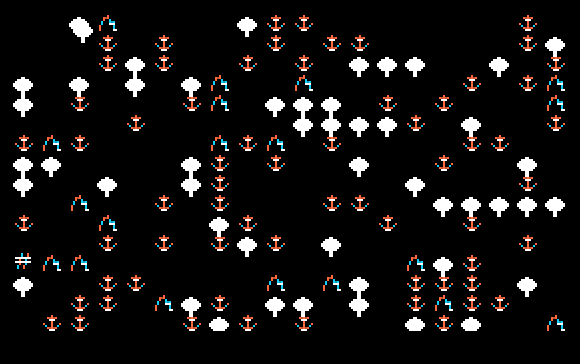

This kind of gameplay, I would argue, makes The Prisoner one of the most immersive video games ever created, even 40 years after publication. The game is directly playing against you, and is devious enough to use that fact against you. Or even consider the town hall segment of the game where you are tasked with managing the Island’s resources as if you were #2. If you decrease surveillance below 100% you start to lose information. Maybe now you only know how much water we have on the Island every 10 seconds instead of every 1. Maybe you can’t tell if someone’s trying to escape and has killed one of your guards, so your guard number is no longer updating. It cunningly puts you in #’s shoes, forcing you to make the decisions as he would, with the same information. Which is really what the game is all about, lest we forget that the game is simply trying to get you to input a random three number string that it gives you at the start of the game. Obviously the game knows what the string is, it generated it for you, but that’s not the point. You become so thoroughly convinced that that #2 in the game is trying to get you that you guard that number like it’s your life. I know I did. Many times. Whenever I would get stuck though, in a puzzle I couldn’t defeat, or as in my last post an infinite loop I could not escape, I would input the code and try again from the top.

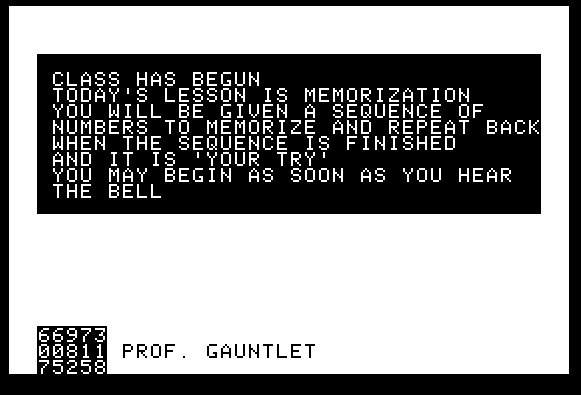

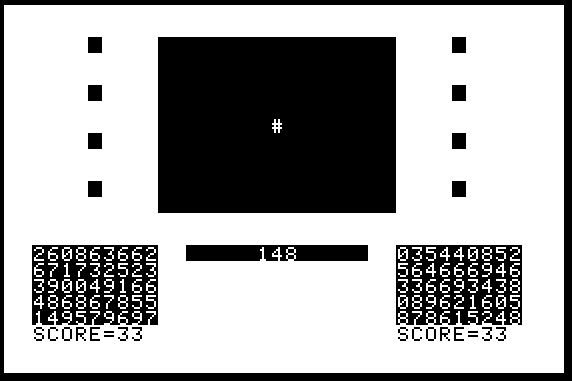

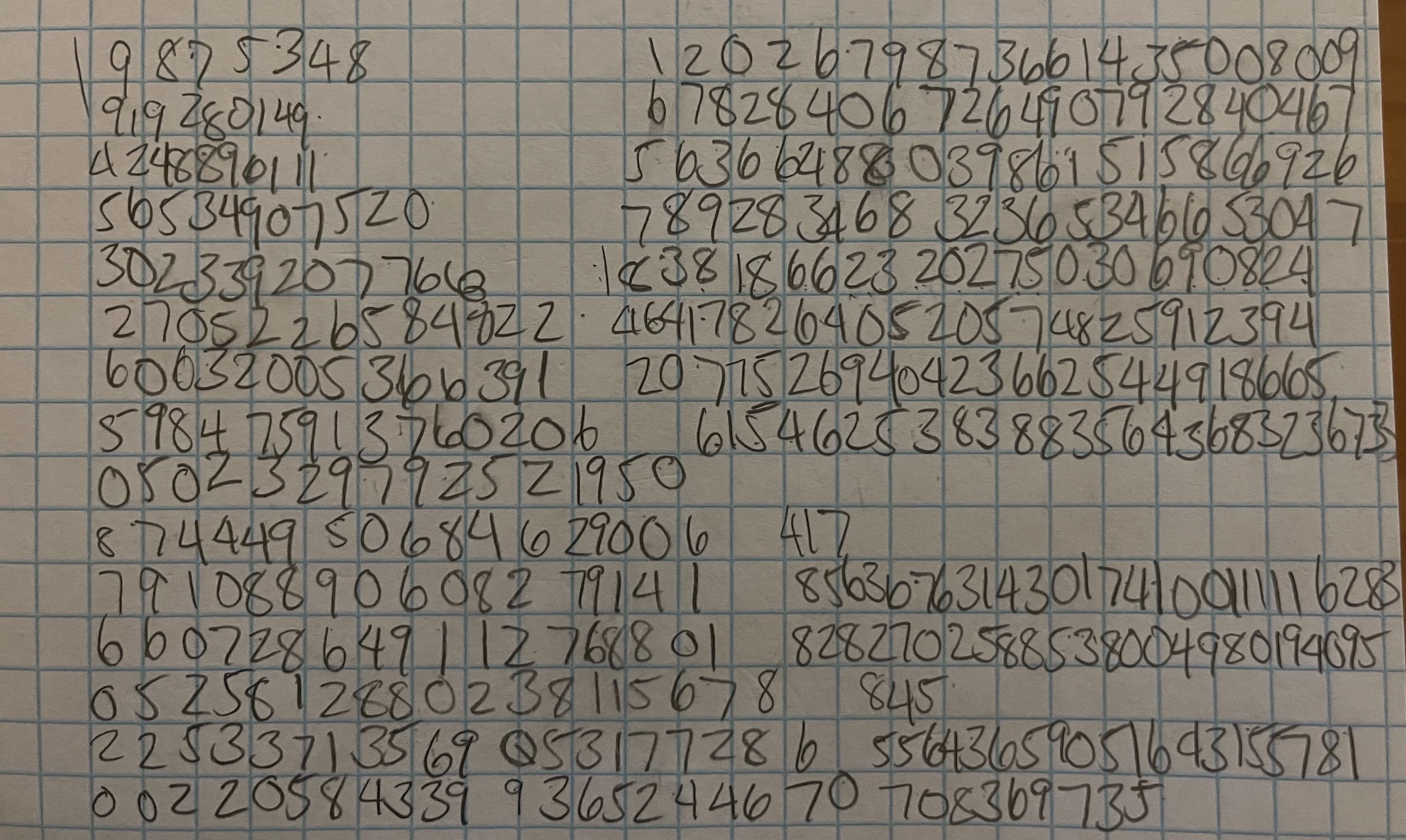

If there was one criticism I could level at the game, it’s that some of the minigames are just ridiculously overlong. For example, the schoolhouse. In the schoolhouse you’re presented a memory challenge, where you have to remember a sequence of numbers that appear on screen and then input them back. Each time you get it correct the length of the sequence increases by one. It decreases if you get a digit wrong, and your goal is to get up to.. I don’t know. I gave up at 30 digits long, and that alone took me well over 35 minutes to get to that point. It’s really slow because you have to wait for each digit to display before you can put the next. It’s horribly contrived and by 10 digits long I was writing down the sequences to make sure I wouldn’t make any mistakes. And then if you did make a mistake you still had to enter the required number of digits before the game would proceed. There were oft times at 20 digits I would mess up digit 4 and sit there spamming the 1 key until it gave me a new sequence. It does try to trick you at 25, where it gives you a three digit sequence that’s your retirement reason, but then it pops up to 26 when you put in some other random string of numbers (which I did). I mean, I get the desire to make the player really feel beat down like 6 was, but at the same time I just don’t have an hour to dedicate to inputting numbers into a computer game.

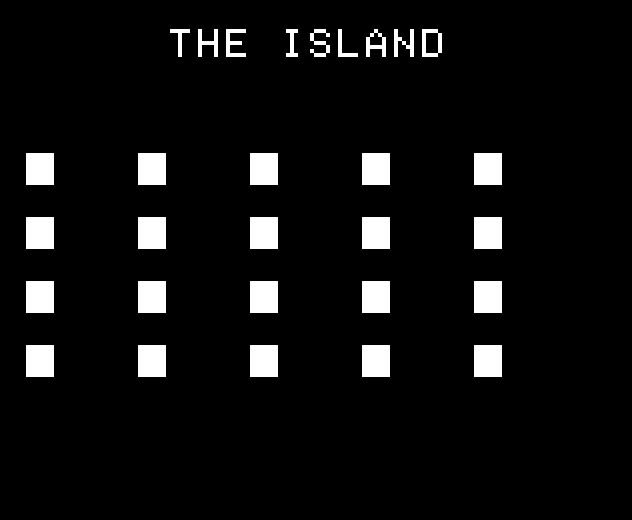

Which actually brings me to what I wanted to talk about, which is that The Prisoner is a really interesting video game adaptation of a visual property because it doesn’t ever directly adapt anything from the TV show. Sure the leader of the island lives in house number 2 and you live in house 6 and there are other suitably subtle but equally as interesting references to the television show that a well versed fan will pick up on. But you’re never actually playing as Patrick McGoohan, or Leo McKern for example. You don’t even live in The Village, it’s the Island. And yet somehow the game feels like the most faithful adaptation of a popular property that I’ve ever played.

I think the reason for that is the incredible job that The Prisoner does in adapting the feeling rather than the content of the product its adapting. Batman: Arkham Asylum is an equally successful adaptation because instead of trying to adapt a specific Batman story they made a game that focuses on giving you the feeling of playing as Batman.

One of the most successful elements of the game is the lingering paranoia that it imbues you with. Like the sequence of memorization above, every time a new sequence comes up you’re not just focused on memorizing it to get it right, there’s always a lingering thought in the back of your mind, checking every three digit string trying to see if it has your resignation in it. And that just makes it harder to memorize which makes it harder to progress so you get frustrated so you stop paying so much attention to whether or not your resignation appears in the sequence.

For some reason you’re always aware of being watched in the game. Just like how #6 is being watched for the entirety of his stay. But the comparisons go deeper. #6 is aware of his surveillance, and uses it against #2 (see Hammer into Anvil). And #2 in reciprocation is aware that #6 knows and uses that information against him. Now play The Prisoner. The video game is completely aware that you’re playing a video game and it uses that against you! Not just in the now famous fake crash. On occasion the game will recognize and admit that you’re playing a video game. Weren’t paranoid before? Now you are. Now the game recognizes you’re playing it just as much as it’s playing you. If that doesn’t drive you to the breaking point what will?

There’s a really bizarre sense of unease in knowing that the game is blending into the real world. You start to feel like there isn’t really a division anymore between the game and your real life anymore. When the game starts to mimic OS functions the line between “the game” and “not the game” blurs, disappearing almost completely. This is where I think The Prisoner exceeds expectations when it comes to metafictional video games. It reaches levels beyond that of many other video games by turning your entire computer into a potential battlefield. Just like when #6 is in the village, you can never let your guard down. You insist over and over that you’re a free man, but at the end of the day you lie down defeated, knowing that you’re not. Because you’re always wondering if the game is still trying to find out why you resigned. Which, by the way, why did you resign?